Metal Gear Solid and its sequels are seminal titles in the history of video games, pioneering the 3D stealth-action genre in conjunction with an ambitious approach to cinematic storytelling. Replaying them again after more than 15 years put me in a state of constant surprise as I was reminded how much each game is still ingrained in the recesses of my brain. From finishing lines of dialogue I hadn’t heard since the PlayStation 2 was brand-new to being able to navigate the winding corridors, air vents, and layered depths of Shadow Moses and Big Shell like the back of my hand–it’s clear how much of an impact the series had on my youth, and I know I’m not the only one. Because of this, the Metal Gear Solid: Master Collection Vol. 1 feels important, both as a means of historical preservation and as a nostalgia-fueled time machine for one of the most influential series of all time.

Konami has certainly assembled an impressive assortment of games for this bundle, beginning where it all started for creator Hideo Kojima. The original 8-bit Metal Gear and Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake–as well as the standalone NES version of Metal Gear and the non-canonical sequel, Snake’s Revenge–are all included in the Master Collection. Having been released in 1987 and 1990 for the MSX2 computer platform, Metal Gear and Metal Gear 2 are showing their age–though surprisingly not to the point where their archaic design renders them unplayable. Played from an overhead 2D perspective, ranged combat is inherently clunky due to your restrictive four-way movement, and any missteps are at the mercy of an unforgiving checkpoint system. Despite these flaws, however, there aren’t many aspects of either game that feel so antiquated that you can’t get something positive out of playing them. It helps that the controls have been updated and unified for this collection, with both triggers letting you access either the items or weapons in your inventory, much like they do in the Metal Gear Solid games. Other than this, Metal Gear and Metal Gear 2 are unchanged from the originals.

More than anything, revisiting the series’ humble beginnings essentially functions as a virtual museum, providing you with a fascinating look at how familiar elements began and then evolved as Metal Gear made the monumental shift to 3D. Both games–particularly Metal Gear 2–feel like blueprints for what was to come, establishing the foundations for Metal Gear Solid and stealth-action video games as a whole. Codec conversations, alert statuses, enemy-identifying radar, and gameplay concepts such as crawling through vents and using sound to draw the enemy’s attention were all part of the series’ roots over 33 years ago. Even if you have no interest in seeing either game through to completion, it’s worth at least giving them a try to see where Metal Gear got its start.

As far as appetizers go, Metal Gear isn’t a bad start, but the main course of the Master Collection is undoubtedly the first three Metal Gear Solid games. The first in the series, originally released in 1998, is the most significant of the bunch, mainly because–outside of a PC release on GOG and its inclusion on the PlayStation Classic–it hasn’t been readily available since it was sold digitally for the PS3. The Master Collection version is also virtually unchanged from the original release, still displaying natively in a 4:3 aspect ratio with blocky PS1 textures that mean Snake barely has a distinguishable face. You can choose to align your display area to the left, right, or center, and there are multiple wallpapers to choose from to fill in the blank areas of the screen (including simple black borders,) so you have options for modifying the smaller aspect ratio to suit you.

The dated visuals are also inherent to the experience. Maybe that’s nostalgia speaking, but Metal Gear Solid hasn’t lost any of its atmosphere in the 25 years since its release. From the opening vocals of “The Best is Yet to Come” to discovering the gory aftermath of Gray Fox’s handiwork, MGS is bursting at the seams with memorable moments that transcend the limitations of its original hardware. It’s also still an excellent game to play, aided somewhat by its use of fixed camera angles. Not only does this decision contribute to the game’s cinematic stylings, allowing certain scenes to be framed with an eye for cinematography, but it also avoids the awkward camera controls that afflicted many early 3D games. Back in 1998, developers hadn’t quite figured out how to handle manual camera control because not every controller had dual thumbsticks. A lot of these games are overly cumbersome to play nowadays, but MGS doesn’t have this issue. Combat is still a tad fiddly because there’s no manual aim, and running and gunning requires you to hold down two buttons at the same time, which isn’t the most intuitive option, but it’s all still manageable.

The Master Collection gives you a chance to appreciate the series’ evolution. Going from MGS on the PS1 to the PS2’s Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty shows an obvious leap in myriad areas. The addition of first-person aiming introduced the ability to fire your weapon with precision, solving one of the first game’s aforementioned restrictions. The improvement in visual fidelity is also startling, although the version included here isn’t the original PS2 release but rather Bluepoint’s superb remaster from the Metal Gear Solid HD Collection. Playing on PS5, both MGS2 and Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater output at 1080p and run at 60 frames per second, and they include the additional features initially present in the Substance and Subsistence editions of each game. This means you can opt to play Snake Eater with the original fixed camera or the much-improved third-person camera, which gives you full control on the right analog stick.

The visuals still fall well short of today’s standards, but I’m in favor of retaining as much of the original games as possible. This doesn’t mean Konami had to leave them alone completely, though. Other similar collections have added optional visual improvements, allowing you to swap between the original game and an updated version with greater graphical fidelity. Maybe this doesn’t make sense in Snake Eater’s case since a fully-fledged remake is already in development, but the Master Collection would’ve been elevated by including some optional advancements to modernize MGS and MGS2.

I spent countless hours playing the MGS2 Tanker demo back in 2001 and immediately fell back on old habits revisiting that opening sequence in the Master Collection: shooting the bottles of alcohol behind the bar; kicking locker doors off their hinges until they crushed me; holding up guards with a tranquilizer gun and forcing them to shake to drop their dog tags; hiding in a cardboard box in the pantry to avoid the guards clearing the room; shooting an enemy’s radio to prevent them from calling in reinforcements. The attention to detail is impressive and a lot of this still feels novel today, like alerting an enemy because Snake couldn’t hold in a sneeze after being outside in the freezing rain for too long. I’m still not quite over Kojima pulling the rug out from under our feet by replacing Snake with Raiden once the game moves to the Big Shell, mostly because the white-haired pretty boy is still as irritating today as he was back then. The way it subverted expectations as a prescient sociopolitical commentary would become a precursor for the rest of the series.

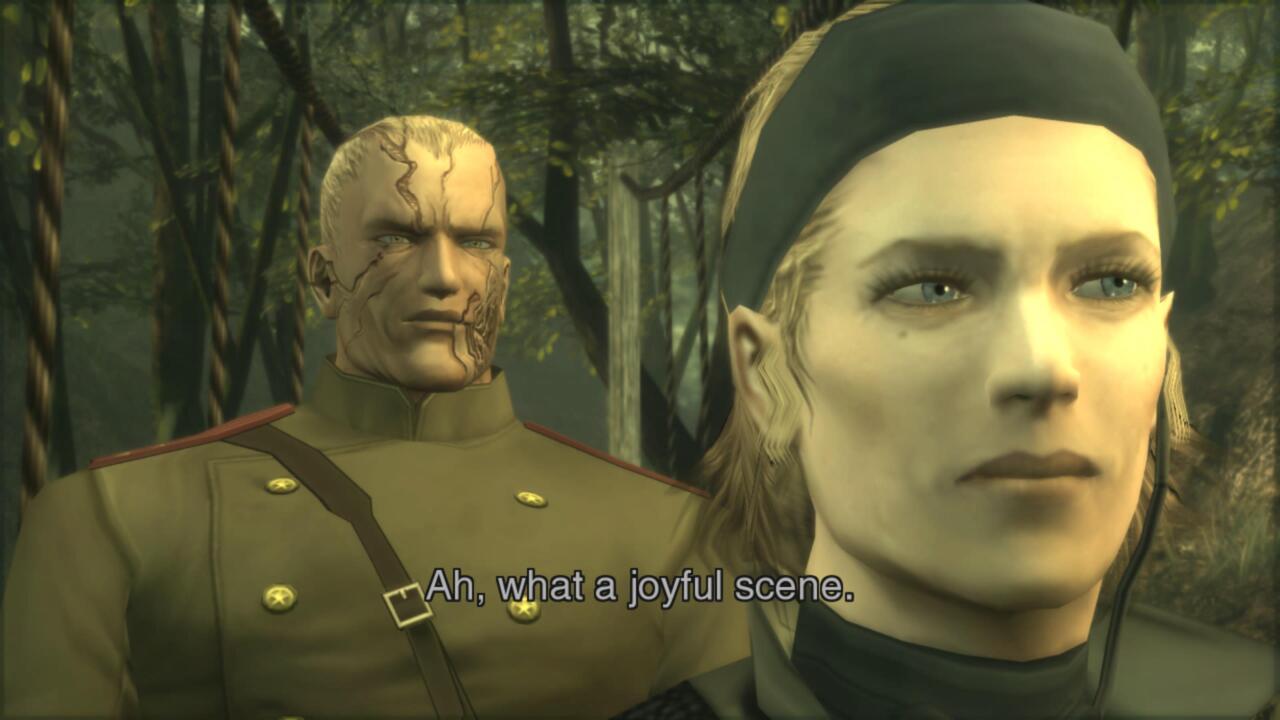

MGS3, Snake Eater, took the action back to the ’60s and ditched the radar in favor of an ambitious camouflage system that allowed you to switch outfits and seamlessly blend into its forested environments. The series veered more heavily into the absurd beginning with MGS2, from introducing a seemingly immortal vampire–who nonetheless earned the name Vamp because he’s bisexual–to a villain being possessed by an arm, and a ghost whose boss fight revolves around walking down an otherworldly river and being haunted by all of the people you’ve killed. With this absurdity, the series also became much more verbose, delving into lengthy expositional tangents, often over-explaining simple concepts and veering wildly between political intrigue, science-fiction, melodrama, and tongue-in-cheek humor. Kojima’s eclectic style is part of the series’ charm, but there are times when it can feel overbearing. Snake Eater’s opening is one such example, as it drags on for far too long, unevenly skewing the cutscene-to-playtime ratio in the former’s favor. Fortunately, once the setup is done, Snake Eater leaves you alone with very few prolonged interruptions. Yet it’s worth noting that the series is infamous for its long-winded cutscenes for a reason.

Konami has added the option to pause cutscenes in a roundabout way, but it only works in Metal Gear Solid. Pausing in the original 1998 release didn’t provide you with any options, so Konami has added what’s called a Stance Menu so you can view an online manual, change various controller settings, fiddle with the display area, and so on. The fact that accessing this menu pauses the game–even during cutscenes–is a useful side effect, but one that doesn’t transfer to MGS 2 or MGS3.

There aren’t any noticeable changes to the original games aside from this. As a result, each one begins with a content warning, noting that some of the game’s “expressions and themes may be considered outdated” but “have been included without alteration to preserve the historical context in which the game was made and the creator’s original vision.” While this doesn’t point to any specific examples, it doesn’t take long before Snake’s hitting on the first two female characters you meet in the original Metal Gear Solid. There’s also a plot point that centers on the shape of Meryl’s posterior, leering shots of Eva’s cleavage in Snake Eater, discussions of some heavy incest themes, and a scene where the president grabs Raiden’s crotch unprompted to confirm his sex, to name just a few controversial and outdated moments. These instances are cringy, gratuitous, and sometimes uncomfortable, but I also think Konami’s approach is the correct one, otherwise each game would have to be significantly altered.

Aside from the core games themselves, there are also several bonus goodies included in this bundle. Metal Gear Solid comes packaged with VR Missions, Special Missions, and Integral. The latter was never released outside of Japan because most of the changes were already implemented in the Western release of MGS, but it’s still a notable piece of digital memorabilia. It’s a shame there isn’t any behind-the-scenes material included in this collection. YouTube is home to various “Making Of” videos, so even if there wasn’t any new material to include, it would’ve been nice if these videos were featured and output at a higher quality. Each game does come with a wonderfully in-depth Master Book that features pages upon pages of information on every game in the series, character biographies, story synopses, details on various gameplay mechanics, and so on. Screenplay Books, on the other hand, detail all of the dialogue in each game, while the digital graphic novels for MGS and MGS2 feature animations, sound effects, and music for the full experience.

Accessing all of this content is a little messy because the collection isn’t assembled in one convenient place. Instead, each part has to be downloaded separately and exists as its own app, independent of the rest. Bonuses such as the graphic novels and VR Missions even have to be downloaded as free DLC, which has presumably been done to keep file sizes down. This is a positive in some ways, as it means you can simply download the games you want to play without the rest eating up valuable hard drive space, but it would be easier to access everything if it weren’t compartmentalized. There are some conspicuous omissions, too, such as Peace Walker, which was included in the HD Collection but doesn’t make the cut here, and rarities like Twin Snakes and Acid that are still confined to the GameCube and PSP respectively. Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots also falls into this category, seeing as the only way to play it is on the PS3. The Vol. 1 designation indicates that there may be a second Master Collection, ideally including all of these games, but we’ll have to wait and see.

Konami has still put together a comprehensive bundle, collecting five highly influential games (and multiple variations) from a period spanning 24 years. There are other ways to play these games, but I think we often undersell the appeal of convenience. Being able to easily access them all on a modern console is a major selling point. For someone like me, who only ever owned the original games on their original consoles, Metal Gear Solid: Master Collection Vol. 1 is indispensable. It’s disappointing that there aren’t any optional visual improvements or behind-the-scenes material, and the lack of a central hub makes the bundle feel scattershot. The bonus content that is here is simply a cherry on top, however, lending the entire package a sense of reverence for one of the most important series in video game history.